Solving NIST Password Complexities: Guidance From a GRC Perspective

Not another password change! Isn’t one (1) extra-long password enough? As a former Incident Response, Identity and Access Control, and Education and Awareness guru, I can attest that password security and complexity requirement discussions occur frequently during National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) assessments. Access Control is typically a top finding in most organizations, with the newest misconception being, “NIST just told us we don’t have to change our passwords as often and we don’t need to use MFA or special characters!” This is almost as scary as telling people to put their Post-it notes under the keyboard so they’re not in plain sight.

In an article Titled, "NIST-proposes-barring-some-of-the-most-nonsensical-password-rules", it was stated that NIST’s “. . . document is nearly impossible to read all the way through and just as hard to understand fully.” This is leading some in the IT field to reconsider or even change password policies, complexities, and access control guidelines without understanding the full NIST methodology.

This blog post will provide an understanding of the context and complexities of the NIST password guidance in addition to helping better guide organizations in safe password implementation guidance and awareness. No one wants to fall victim to unintended security malpractice when it comes to access control.

Understanding the NIST Password Guidance in Context

The buzz around the NIST password guidance is frustrating because everyone seems to zoom right down to the section with the password rules and ignore the rest of the guidelines. The password rules are part of a much larger set of digital identity guidelines, and adopting the password rules without considering their context is counterproductive and potentially dangerous.

The Scope and Applicability section of the new NIST guidelines, formally known as NIST Special Publication 800-63 Digital Identity Guidelines (NIST SP 800-63), states “These guidelines primarily focus on organizational services that interact with external users, such as residents accessing public benefits or private-sector partners accessing collaboration spaces.” In plain English: the guidance in NIST SP 800-63 is not intended for internal users’ accounts or sensitive internal systems, and organizations implementing the password rules on their internal systems are misusing the guidance.

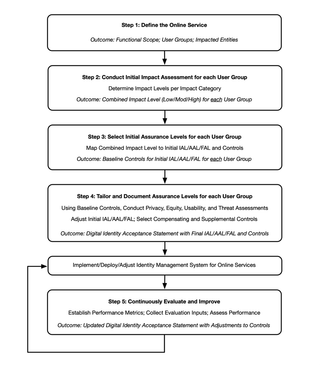

For organizations that are planning to use this guidance to secure their external-facing service accounts, NIST SP 800-63 spends 26 pages defining a risk-based process for selecting and tailoring appropriate IALs, AALs, and FALs, respectively, for systems, with three (3) assurance levels defined in each of those categories (see NIST SP 800-63 Section 3). It goes on to provide guidance on user identification, authentication, and federation controls appropriate for each assurance level in three (3) additional documents—NIST SP 800-63A, B, and C, respectively.

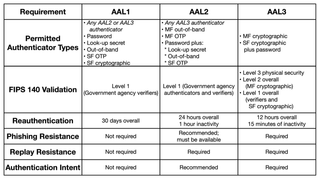

The new password guidance is meant to support the AALs (defined in NIST SP 800-63B). Only AAL1, the lowest of the AALs defined in the guidelines, allows passwords to be used alone and still states that multi-factor options should be available.

AAL1 is defined as providing “basic confidence that the claimant controls an authenticator bound to the subscriber account.” Organizations that adjust their rules for passwords to match the NIST guidelines without performing the risk-based analysis and selecting an appropriate AAL are naively implementing what NIST intended only for the most basic protection. This is an inappropriate use of this guidance document, as many systems will present significantly more risk to the organization than AAL1 was designed to address and would be more appropriately protected by AAL2 or AAL3 controls.

In short, the NIST SP 800-63 password guidance (when used properly with a risk analysis) is intended and appropriate for external user accounts on public-facing services, e.g., customer accounts on a public portal. However, organizations should think twice before applying it to their own internal systems and users, because that was not its intended purpose.

It’s also worth pointing out that, as of this post, the guidance that is making so many headlines is a draft and is subject to change before finalization.

Using the NIST Guidance

The two (2) most frequently asked password questions as auditors or GRC consultants we get at TrustedSec are, “Do we really need Multifactor Authentication (MFA) everywhere?” and “What is the best practice for the implementation of passwords?”

For any organization that logs into a network, starting with a framework is a must for successful governance and cybersecurity foundations. Additionally, organizations must adhere to password and access guidelines based on the legal and regulatory requirements they must follow to keep their businesses running. Some examples are various NIST security control frameworks (e.g., CSF or SP 800-171), PCI-DSS, HIPAA, NERC-CIP, ISO 27001, SOX, etc.

Many of these frameworks include specific requirements for utilizing complex passwords, rotation of passwords or passphrases, enabling MFA, determining access levels, and performing access reviews appropriate for the types of information and/or systems these frameworks are designed to protect. This NIST SP 800-63 guidance does not in any way override or supersede any of these more specific requirements, so organizations should continue meeting existing framework requirements.

You might be asking, “How does this apply to my organization?” Most organizations question if their situation is applicable, due to the term “online service.” In today’s society, when users think of an “online service,” most would think shopping portals or online goods. However, as NIST defines it in the Glossary of SP 800-63, an online service is “A service that is accessed remotely via a network, typically the internet.” This is important to clarify that any organization that has an Internet-facing network is using an online service and can adhere to the digital guidelines and implement best practices for security, based on their risk profile or digital risk in the absence of other compliance requirements.

What is digital risk? NIST describes Digital Identity Risk as management flow to help perform the risk assessment or risk impact. As seen with the new release of NIST CSF 2.0, Governance and Risk Assessments are the core to a healthy cybersecurity program.

Organizations can begin to perform the risk (impact) assessment, as defined in SP 800-63 Section 3, by defining the scope of the service that they are trying to protect, identifying the risks to the system, and understanding what categories and potential harms the organization possesses. Identifying the baseline controls to use in the risk formula will assist with selecting the appropriate level.

The three (3) key components are:

- Identity Assurance Level (IAL)

- Authentication Assurance Level (AAL)

- Federation Assurance Level (FAL)

Identity Assurance or proofing is about a person proving who they say they are. A useful example: I sign up for a web service and enter an email address and new password—how does the service know I actually control that email? If they're smart, they will send a confirmation email to that address before setting up the account to prove my identity. This gets more complex when a user ID needs to be associated with a specific named individual, e.g., when retrieving medical information from a portal.

Authentication is the process of confirming a user’s identity prior to allowing them access to a system or network, such as through a password.

Federation is a process that allows access based on identity and authentication across a set of networked systems.

Each level will have a severity rating, e.g., Low, Moderate, or High. Starting with the user groups and entities, thinking of people and assets, and then determining a category or categories will help identify harms or risks. Some examples are listed in SP 800-63.

Next is evaluating the impact that improper access would have on an organization. This assists in identifying the impact level. Impacts such as reputation, unauthorized access to information, financial loss/liability, or even loss of life or danger to human safety can be included to help determine the impact level for each user group and organizational entity.

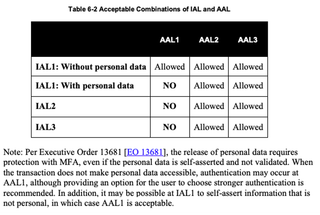

Using the impact level leads to determining the IAL and then the AAL. When determining the AAL, the intent is to mitigate risk from authentication failures such as tokens, passwords, etc., whereas IAL is aligned with identity proofing and individuals. Certain factors, such as privacy, fraud, or regulatory items, may require a specific AAL. NIST references these in SP 800-63A, SP 800-63B, and SP 800-63C.

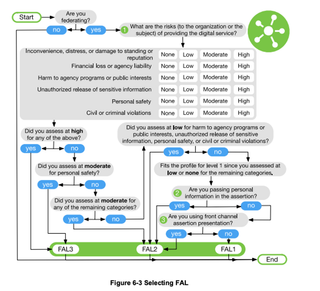

Once the AAL is established, referencing SP 800-63C can be helpful in the next step for selection of the FAL. This assists in identifying the identity federation, which uses the Low, Moderate, and High impact criteria.

Once IAL, AAL, and FAL have been established for each user group or entity, an Initial AAL can be selected. Of course, this will also need to take into consideration baseline controls, compensating controls, or supplemental controls, if needed.

Also keep in mind, as with all NIST processes, that continuous evaluation and improvement are critical to staying secure, making this a recurring process.

The NIST flow diagram for the Digital Identity Risk Management Process is as follows:

Now that the calculated AAL has been established, the chart in Section 3.5 of SP 800-63b will help with understanding some of the requirements.

Most systems would be a Level 2 or 3, considering what the organization would be storing, processing, or transmitting. Things like sensitive data such as personally identifiable information (PII) during onboarding, payment card data, and PHI subject to HIPAA for places like hospitals or service providers might help align with each AAL.

Instances where Level 1 might be utilized could be a website that would not store payment data but requires a user to log in with a user ID and password. Understand that risk for the website is minimal, and therefore a Level 1 for that specific system may be deemed appropriate. But the organization may have corporate network controls set to Level 2, due to HR or doing business with certain service providers. It’s perfectly fine to have various levels assigned to different groups and assets or entities.

A similar process to define the IAL and FAL as noted in NIST’s Digital Identity Guidelines (NIST SP 800-63-3) is depicted below:

IAL:

FAL:

So, after all of this, is one (1) super-long password really enough? It depends on the AAL and what other legal and regulatory requirements an organization is expected to adhere to. The highest level should always be implemented where possible, if the risk is present in the organization. For example, if the organization processes credit card data, PCI-DSS standards would prevail, meaning that passwords pertaining to the CDE must follow all PCI guidance and likely would be considered a Level 3 after performing the risk assessment. The key to the AALs, really, is determining the most sensitive data our organization has and aligning it with that level.

Now, let’s put the AAL to use. I always consider Incident Response and Education and Awareness as my lead examples behind why we do security. If an organization becomes compromised, are all passwords and access controls properly aligned with the risk, and do they adhere to all legal and regulatory controls?

Lastly, always implement MFA where possible; after all, NIST does strongly suggest it SHOULD be available, even at AAL 1! Be proactive on how to report an incident if your password is suspected to be compromised, change it immediately—even if NIST has a different idea—and communicate it to all users. All users and organizations should understand the risk to their specific organization and be compliant. Security is everyone’s responsibility—don’t let your organization’s password hygiene be the cause of the next big breach.