Holy Shuck! Weaponizing NTLM Hashes as a Wordlist

Table of contents

Password reuse is common in Active Directory (AD). From an attacker’s perspective, it is a reliable path to lateral movement or privilege escalation. Most IT teams recognize the risk, but longer passwords and password managers encourage the belief that reusing a long password is safe. Once passwords reach high character lengths, recovering them is usually impractical for many hash types, and that reuse often slips by unnoticed.

Enter hash shucking. Instead of trying to recover plaintext passwords from slower algorithms like Kerberos tickets or cached credentials, we can use NTLM (NT) hashes as a wordlist in Hashcat’s NT Modes. This lets us quickly validate password reuse across NTLMv1 and NTLMv2 challenge-responses, Kerberos 5 etype 23 tickets, and DCC/DCC2 hashes. If a match is found, we can spend time more effectively by recovering the plaintext from the NT hash, or by using pass-the-hash (PtH). In this post, I describe hash shucking and its relevance to AD, outline the key Hashcat modes involved, demonstrate the technique with two examples, and close with practical mitigations to limit opportunities for hash shucking.

What is Hash Shucking?

Say a company runs two sites. Site A is breached and exposes unsalted MD5 hashes:

md5(password)Later, Site B upgrades the password storage by wrapping existing passwords with bcrypt. It is also breached, exposing:

bcrypt(md5(password))With the MD5 hashes from Site A and the bcrypt-wrapped MD5 hashes from Site B, you can take the MD5 values from the Site A breach and supply them directly to bcrypt:

bcrypt(md5hash)If the bcrypt check matches, we have confirmed the same password is reused without ever recovering the plaintext. This is hash shucking: the outer layer (bcrypt) is shucked off, and you can run password-recovery attacks against the inner hash (MD5) at much higher speeds. I recommend checking out What the Shuck? Layered Hash Shucking by Sam Croley for a more detailed explanation.

How This Applies to AD

Passwords in AD are stored on domain controllers as NTLM hashes. The NT hash is computed as MD4 over the UTF-16LE encoding of the password.

MD4(UTF-16LE(password))Kerberos supports multiple encryption types. When RC4-HMAC (etype 23) is allowed, TGS tickets can be requested that are encrypted with a key derived from the target account’s NT hash. Using any domain user, you can request a TGS for an account with an SPN, capture the resulting TGS-REP, extract the RC4-based TGS-REP hash, and take it offline for password recovery.

RC4-HMAC(MD4(UTF-16LE(password)))If an NT hash supplied as the candidate verifies a TGS-REP hash, you’ve proven the same password was used. From there you can shuck the outer layer and either recover the plaintext from the NT hash or skip recovery and use PtH.

This shucking approach also works wherever the NT hash is the underlying key. That includes:

- NTLM challenge-responses: NTLMv1 and NTLMv2

- Kerberos 5, etype 23 tickets: AS-REQ Pre-Auth, TGS-REP, and AS-REP

- Cached credentials: DCC and DCC2

Note: Kerberos 5, etype 23 AS-REQ pre-auth does not have an NT-candidate mode in Hashcat at the time of this writing.

To Shuck or Not To Shuck

Hash shucking can save significant time when an AD environment contains password reuse. Instead of burning compute on slow formats, you can quickly confirm reuse across multiple targets by testing NT hashes as candidates. Those NT candidates are best when they come from the same AD environment. The most fruitful source is an NTDS extraction from a domain controller, which typically yields thousands of hashes. Windows endpoint SAM/SECURITY hive extractions are also usable, but usually less valuable because of LAPS and infrequent local-account use. This technique is especially valuable in multi-domain or trust scenarios: if you control one domain and have its NT hashes, and can capture NT-based hashes in another, shucking lets you validate reuse quickly and prioritize high-value lateral movement targets.

You should attempt shucking whenever you possess NT hashes and an NT-based target. Even an otherwise infeasible 60-character passphrase can be validated for reuse if you have the corresponding NT hash. From there, you can recover the plaintext offline from the NT hash or use the NT hash directly for authentication via PtH.

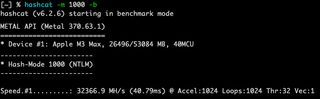

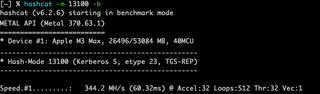

Attacking the NT hashes is much faster. On an Apple M3 Max, Hashcat NTLM (mode 1000) runs at roughly 30,000 MH/s while TGS-REP (mode 13100) runs at about 300 MH/s, roughly a 100x speed advantage. While that gap doesn’t account for the time spent testing for reuse, running Hashcat’s NT-hash modes against NT-based captures adds only minimal extra runtime.

But all this shucking fun does have its limits. Kerberos 5 etype 17 and 18 aren’t derived from the NT hash, so NT-based shucking doesn’t apply to them. If the AD domain is enforcing AES and you can’t request RC4/etype 23, you have to fall back to normal password recovery and use the AES Kerberos modes in Hashcat, for example 19600 for etype 17 (AES128) and 19700 for etype 18 (AES256).

Ultimately, hash shucking is best when the NT hashes come from the same environment you are testing. You could use large lists from data breaches and potentially find a match, but that approach is time-consuming with a low likelihood of success. Hashcat’s NT shucking modes aren’t faster than the normal password modes, and because you’re feeding fixed 32-hex NT hashes, applying wordlist rules mangles the hashes and they no longer represent the original passwords.

Hashcat Shucking Modes

For quick reference, the table below lists Hashcat password modes alongside their corresponding NT-based shucking modes.

Hash Type | Mode (password) | Mode (NT) |

|---|---|---|

Domain Cached Credentials (DCC) | 1100 | 31500 |

Domain Cached Credentials 2 (DCC2) | 2100 | 31600 |

NetNTLMv1 / NetNTLMv1+ESS | 5500 | 27000 |

NetNTLMv2 | 5600 | 27100 |

Kerberos 5, etype 23, AS-REQ Pre-Auth | 7500 | N/A |

Kerberos 5, etype 23, TGS-REP | 13100 | 35300 |

Kerberos 5, etype 23, AS-REP | 18200 | 35400 |

Demo Time

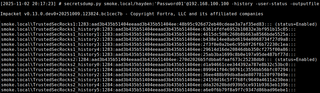

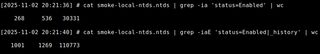

For these demos, SMOKE.LOCAL is assumed to be compromised, and NT hashes are obtained via a DCSync attack using Impacket's secretsdump.py:

secretsdump.py <domain>/<user>@<ip> -history -user-status -outputfile <output.txt>

When you perform DCSync attacks, you should target password history as well. With secretsdump.py, this is done using the -history flag. Microsoft recommends keeping up to 24 previous passwords in history to reduce reuse, but from an attacker’s perspective this significantly increases the number of NT hashes obtained. Users will not always have a full history, but even a few historical passwords per account can greatly expand both the number of recovered passwords and the NT hash wordlist used for shucking. The same logic applies when you dump SAM on Windows endpoints with Mimikatz or similar tools: historical hashes give you more candidates for shucking and reveal password-change patterns you can use to predict likely current passwords.

Lastly, make sure you are using the latest version of Hashcat, as the NT-based shucking modes used in the following demos require newer releases.

Demo 1: Kerberoast Scenario

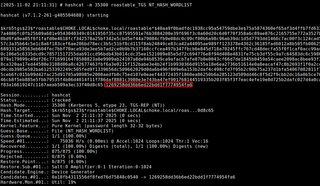

For this demo, a Kerberoast attack is performed against CHOKE.LOCAL using a low-privileged user. Impacket's GetUserSPNs.py is used to request a service ticket for the CHOKE.LOCAL\roastable account, which returns a Kerberos 5 etype 23 TGS-REP hash. That hash is saved to roastable_TGS, and the $krb5tgs$23$ format indicates it is RC4-based.

GetUserSPNs.py -dc-ip <dc_ip> -request <domain>/<user>

Next, Hashcat is utilized in NT-candidate mode 35300 using the TGS hash from CHOKE.LOCAL and the NT hash wordlist obtained from SMOKE.LOCAL. Hashcat is able to match the TGS-REP against an NT hash in the wordlist, showing that the CHOKE.LOCAL\roastable account is reusing a password.

hashcat -m 35300 <hash_file> <nt_wordlist>

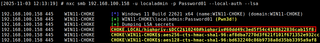

That NT hash is then used via NetExec to authenticate over SMB to the CHOKE.LOCAL domain controller as CHOKE.LOCAL\roastable, demonstrating cross-domain password reuse in practice.

nxc smb <dc_ip> -u <user> -H <NT_hash>

Demo 2: Domain Cached Credentials Scenario

For this demo, an LSA secrets extraction is performed against a domain-joined workstation in CHOKE.LOCAL using localadmin, a local Administrator account. NetExec is used to extract LSA secrets, which includes a DCC2 hash for the CHOKE.LOCAL\highpriv account. That DCC2 hash is then copied into a file named DCC2_hash for offline testing.

nxc smb <ip> -u <user> -p <password> --local-auth --lsa

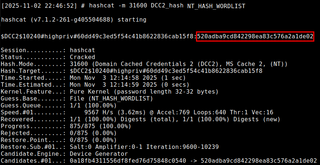

Hashcat is then utilized in NT-candidate mode 31600, using the DCC2 hash as the target and the NT hash wordlist obtained from SMOKE.LOCAL.

Hashcat -m 31600 <hash_file> <nt_wordlist>

Using that NT hash, NetExec authenticates over SMB to the CHOKE.LOCAL domain controller as CHOKE.LOCAL\highpriv, again demonstrating cross-domain password reuse in practice.

nxc smb <dc_ip> -u <user> -H <NT_hash>

Mitigations

Password reuse is the core issue that makes hash shucking possible. User and service accounts should not share passwords across domains, forests, or privilege tiers. Service accounts should use gMSAs or other managed credentials instead of static passwords. Reusing the same secret across multiple accounts effectively removes the separation of privilege those accounts were meant to provide.

Kerberos configuration is a major control point. Environments should prefer AES etypes 17 and 18 and phase out RC4/etype 23 for domain and service accounts wherever possible. After tightening the allowed types, passwords should be rotated so new AES keys are derived and any existing RC4-based tickets become useless.

Local Admin reuse and privileged logons need to be controlled. Local Administrator passwords on endpoints should be managed with LAPS, Windows LAPS, or a similar control so each host has a unique, rotated local Admin credential. Domain Admin and other tier-0 accounts should be restricted from interactive logons on normal workstations so their cached credentials cannot be easily extracted via local Admin access.

Conclusion

As shown in the two demos, hash shucking makes it possible to detect and exploit password reuse without ever recovering the underlying password. The Kerberoast example used the NT hash 1269258dd36b6ed22bdd1f7774954fa6, which is from the password:

Trustedsec**!!TrustedsecTrustedsec@#$&*WOOOOH12345IsAnyoneActuallyReadingThis??That kind of string is effectively out of reach on a normal penetration testing engagement, yet shucking still lets you prove reuse and laterally move. The DCC2 example used 520adba9cd842298ea83c576a2a1de02, a far more realistic password that could be recovered with standard wordlists and rules. I’ll leave that one as an exercise for the reader.

While hash shucking turns NT hashes into a high-value wordlist for other NT-derived formats, it doesn’t replace full password recovery. However, it can deliver quick wins on an offensive engagement by proving reuse and enabling access even when the underlying password is effectively unrecoverable.

Shoutouts

Sam Croley - Original hash shucking research

Team Hashcat - For building and maintaining Hashcat

Justin Bollinger - Blog Review

Hans Lakhan - Sanity-checking terminology and ideas

Additional References

https://github.com/Pennyw0rth/NetExec

https://github.com/fortra/impacket

https://github.com/gentilkiwi/mimikatz

https://github.com/hashcat/Hashcat

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/identity/laps/laps-overview

https://www.scottbrady.io/authentication/beware-of-password-shucking