Government Contractor’s Ultimate Guide to CUI

Table of contents

Contractors and subcontractors working for the US Federal Government (as well as some other unrelated organizations) may encounter contract clauses that require them to protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) but may be confused about what CUI is and how these requirements apply.

These clauses may include mention of one (1) or more of the following:

- Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC)

- Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA)

- Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP)

- Executive Order 13556

- Supplier Performance Risk System (SPRS)

- Various National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) frameworks:

- Various parts of the Federal Acquisition Regulations and its supplements including but not limited to:

There is an increased awareness of CUI and its protection as a result of the upcoming DoD CMMC program. TrustedSec has received many inquiries from defense contractors seeking to prepare themselves for CMMC requirements and in some cases TrustedSec has determined that these contractors are not handling CUI and therefore have no CUI protection obligations.

Organizations that misrepresent their CUI protection program, i.e., claiming CUI protection controls are in place when they are not, are subject to liability under the False Claims Act (FCA). This law allows for a penalty as well as triple damages for any harm caused to the Government. The law also allows private citizens (i.e. whistleblowers) to file suits on behalf of the government and receive a portion of what the government recovers as a result. Settlements and judgements under the FCA exceeded $2.68 billion in 2023 including a $4 million settlement for failing to satisfy cybersecurity controls. Contractors must take the protection of CUI seriously.

This post provides information that can help government contractors understand what CUI is, determine what information they have is CUI (if any), how they must protect that CUI, and how they can use the CUI program to their advantage.

This post starts with some quick tips for identifying and protecting CUI to help organizations get started quickly. This may be useful for organizations attempting to determine if they have any compliance obligations related to CUI. The remainder of this post takes a deep dive into the CUI program’s origins, structure, and nuances to help contractors that are dealing with CUI gain a more comprehensive understanding of their obligations.

Terminology

Throughout this post the term ‘agencies’ is meant to refer exclusively to executive branch agencies of the United States Federal government and the term ‘government’ is meant to refer exclusively to the United States Federal government unless otherwise indicated.

The term ‘contractors’ is meant to refer to any organization that intends to bid on or has been awarded government contracts either directly with an agency as a prime contractor or indirectly as a subcontractor. The term ‘contracts’ is meant to refer to prime contracts between an agency and a contractor as well as any subcontracts.

The term ‘handling’, as in ‘handling CUI’ is meant to encompass the storage, processing, and/or transmission of information.

The term ‘CUI protections’ and similar terms used throughout this post are meant as shorthand to encompass both the CUI safeguards and limited dissemination controls as applicable in a particular context.

CUI in a Nutshell

It is important to understand that the CUI program was intended to support United States government executive branch agencies sharing information with each other. The requirements of the CUI program, including the definition of CUI, is based on intra-government sharing of information and applicability to contractors almost feels like an afterthought. Much of the confusion around CUI comes from the difference between what agencies must treat as CUI, what contractors must treat as CUI, and the details of the relationship between contractors and agencies.

There is some nuance to CUI program, but the following criteria can be used by contractors to quickly determine whether or not they likely have CUI protection obligations:

- Cloud services used by agencies, including services used by agencies to handle CUI, are addressed under a separate program (FedRAMP) and the CUI program guidance in this post is mostly irrelevant (see the Cloud Service Applicability section of this post for more detail).

- A contractor must have an agreement with an agency to protect CUI for the contractor to have any CUI protection obligations. This is usually accomplished via a contract that contains a specifically worded clause from the Federal Acquisition Regulations or its supplements.

- Any CUI a contractor receives under a CUI protection agreement should be clearly marked by the agency or an upstream contractor using standardized CUI markings before the contractor receives it.

- Information created by a contractor can only be CUI if it was created for the government. The agreement with the agency or the supporting documentation should clearly define the information the contractor will create that must be designated, marked, and protected as CUI.

A contractor has no CUI protection obligations and should not be receiving CUI if there is no agreement with an agency to protect CUI. Even with a CUI agreement in place, information received from the government (including via other contractors) that is not marked as CUI or is created for the government but does not fit the contract’s definition of CUI is not likely to be CUI.

There are a few points worth noting when applying this basic test:

- CUI is not a type of classified information and classified information is never CUI. This is part of the formal definition of CUI and is also right there in the name: Controlled Unclassified Information. However, classified information and CUI may be mixed in the same document.

- Objects are not CUI. Again, it’s right there in the name: Controlled Unclassified Information. An object that was manufactured based on CUI may be covered by other laws or regulations, e.g., International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), but is not itself CUI.

- Some information may be CUI from the perspective of an agency but not from the perspective of a contractor and the contractor is under no obligation to apply CUI protections to such information. This is especially true of the contractor’s pre-existing proprietary information that happens to be sent to an agency.

- Even if information is not CUI, there may be other applicable contract clauses, laws, and/or regulations that apply directly to private organizations handling the information. For example, many government contracts will include a clause for the safeguarding of Federal Contract Information (FCI) which is a much broader category than CUI. These other requirements are beyond the scope of this post.

The details of the compliance scope, safeguards, and any necessary attestations or certifications are defined separately by each agency and are specific to each individual agreement. As a result, these details are beyond the scope of this post, although future posts may address details of the CUI programs of specific agencies. In general, contractors will be required to protect most CUI in accordance with the security controls contained in NIST SP 800-171. Additional safeguards, including controls from NIST SP 800-172 and NIST SP 800-53, may also be necessary for certain specific types of CUI.

The rest of this post will explore these points and their deeper nuances in detail.

CUI History

Understanding how the CUI designation came into being will help understand what information is considered CUI.

Many people are familiar with the idea of classified information, i.e., “Confidential”, “Secret”, and “Top Secret”. There are extensive regulations in 32 CFR Part 2001 that define what information warrants classification and how it must be handled. Agencies often have sensitive information that they want to protect even though it doesn’t meet the threshold for classification. This is where CUI comes in.

Historically, agencies established their own set of policies, procedures, markings, safeguards, and dissemination limitations for unclassified sensitive information that they want to control. This mix of various agency-specific standards made it difficult for agencies to share information with each other, as each agency expected other agencies to adhere to their own unique protection requirements when receiving sensitive information.

In 2010, Executive Order 13556 created the new CUI program with the goal of making it easier for agencies to share information with each other by defining a single standard for safeguarding and marking sensitive information across all agencies rather than having agencies adhere to each other’s ad-hoc standards. Many of the legacy agency-specific designations became a category or subcategory of the new CUI designation.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) was assigned responsibility for managing this new CUI program, with two key responsibilities:

- Creating a CUI registry, listing the different CUI categories and subcategories, markings, safeguarding and dissemination procedures, and decontrol procedures.

- Creating regulations to support the CUI program, which resulted in 32 CFR Part 2002, published in 2016.

These NARA resources are important tools for understanding what CUI is and will be discussed in more detail later in this post.

Agencies have been working to implement their agency-specific CUI programs based on Executive Order 13556 and 32 CFR Part 2002 but the CUI program, and especially its relationship with contractors, is still in its infancy. We can expect the CUI program to expand to more contractors in the future.

Note that both Executive Order 13556 and 32 CFR Part 2002 only apply directly to agencies. These are both useful references for contractors to understand how the CUI program is structured, but the extent of a contractor’s CUI protection obligations is defined solely by their individual agreement with an agency as described below.

Applicability to Contractors

The 32 CFR 2002 CUI regulations explicitly state that they apply to agencies but do not apply to “non-executive branch entities” (which includes private organizations, e.g., contractors) unless those organizations have a specific agreement with the federal government:

This is an important concept to remember as we decide what is CUI: A contractor has no obligation to designate, mark, or protect CUI unless a specific agreement to do so is in place with an agency.

CUI Agreements

32 CFR 2002.16(a)(5) lists the various types of agreements government agencies can utilize, but typically contractors will see these agreements show up as clauses within their contracts and subcontracts. 32 CFR 2002.16(a)(6) lists the information these agreements must include.

Contractors that are on the receiving end of these agreements will find, with a few exceptions, that they are instructed to protect CUI using the controls contained in NIST SP 800-171. NIST SP 800-171 is a framework created as part of the CUI program specifically to define controls for protecting CUI. NIST SP 800-171 is derived from the controls contained in the NIST SP 800-53 framework that the government uses to protect its own systems in accordance with FISMA and only includes controls from the NIST SP 800-53 Moderate Security Baseline that are relevant to non-federal organizations protecting CUI (NIST SP 800-53 also contains Low and High Security baselines).

Each agency must create its own CUI program and agreements. The Department of Defense (DoD) CUI program is perhaps the most well-known and was rolled out in 2020 with a large update coming soon (likely early 2025) in the form of the CMMC program. Many other agencies are still rolling out their own CUI programs and agreement text. There is a possibility of a government-wide default CUI agreement that agencies will be able to use in lieu of agency-specific agreements.

Standardized CUI agreement contract clauses from the agencies that have produced them and the instructions to Federal contracting personnel about when to use those clauses are contained in the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), including various supplements for different branches of the government. The contract clauses are updated from time to time so organizations should watch for changes. The acquisition.gov FAR and supplement pages linked above are a great resource for tracking these changes as it shows when each clause was last updated.

CUI Subcontracts

32 CFR 2002.16(b)(3) specifically states that non-executive branch entities (which includes contractors) may be sub-recipients of CUI from other non-executive branch entities (e.g., prime contractors or other subcontractors) so not all CUI will be received directly from or sent directly to an agency.

Typically, when a contractor wants to share CUI with another organization, they will need to establish a CUI protection agreement with the recipient so that the contractor can be assured that the recipient will meet the CUI safeguard requirements. The agency-specific standardized contract clauses described above usually contain a requirement for contractors to pass the entire clause on word-for-word in any subcontracts that will involve handling of CUI, thereby pushing the same standardized CUI protection obligations down the supply chain.

We can look to the DoD’s new CMMC program as an example of how this works:

- DFARS 204.7503 instructs DoD contracting personnel to insert the contract clause shown at DFARS 252.204-7021 into solicitations and contracts for commercial products and services except for off-the-shelf items.

- Prime contractors that receive a contract with the DFARS 252.204-7021 clause will note that:

- DFARS 252.204-7021(b) requires contractors have a current CMMC certificate at the level required by the contract and maintain it for the duration of the contract (CMMC Level 2 is used for protecting CUI and is based on NIST SP 800-171, Level 3 is based on NIST SP 800-172).

- DFARS 252.204-7021(c)(1) from the contract requires contractors to insert the entire DFARS 252.204-7021 clause into subcontracts.

- DFARS 252.204-7021(c)(2) requires contractors to verify that the subcontractor has a current CMMC certificate at the appropriate level.

- A subcontractor will thereby receive the DFARS 252.204-7021 clause in their contract with the prime contractor and will be required to pass it along to their subcontractors just as the prime contractor did to them. The contractor will also need to ensure the subcontractor has a CMMC certificate, which is unique to the DoD contract clause.

CUI Agreements Without CUI

It is worth pointing out that some organizations, including state and local governments, may include NIST SP 800-53, NIST SP 800-171, CMMC, FedRAMP, or other similar compliance requirements in contracts that have nothing to do with United States Federal government contracts or CUI. This may be a result of the way Federal contracting regulations operate but may also be a result of other organizations misapplying compliance requirements.

Broad Federal Contract Clauses

In theory, CUI related contract clauses should only be passed down in contracts that involve the handling of CUI. However, contracts may have compliance clauses even if no CUI will be handled under the contract. This is especially true of CMMC, as CMMC also applies to FCI even when CUI is not present.

As CUI protection requirements follow the flow of CUI, organizations on the receiving end of these contract clauses will need to understand whether they are handling CUI and how to determine applicability. If there is no CUI handled under the contract, then there is no CUI to protect and, therefore, no scope to which the CUI protection controls can be applied.

We can look to the DoD’s current CUI protection contract clause, DFARS 252.204-7012, to show how an organization can receive a contract with a CUI protection clause even if they have no CUI to protect and therefore no NIST SP 800-171 CUI safeguarding obligations. This requires going through a long chain of definitions:

DFARS 204.7304 requires Federal contracting personnel to insert the DFARS 252.204-7012 clause into all solicitations and contracts for commercial products and services excluding commercial-off-the-shelf items.

- Notably, DFARS 204.7304 does not say a contract must include handling of CUI for the DFARS 252.204-7012 clause to be inserted, so many DoD contractors will have this clause in contracts that have nothing to do with CUI.

DFARS 252.204-7012(b)(2)(i) states that contractors must apply the NIST SP 800-171 safeguarding controls to the “covered contractor information system”.

- Based on this, a contractor must determine if they have a covered contractor information system to determine if there is any NIST SP 800-171 safeguarding obligation and must understand the definition of covered contractor information system to do so.

DFARS 252.204-7012(a) defines “covered contractor information system” as a contractor system that stores, processes, or transmits “covered defense information” (CDI).

- Based on this, a contractor must understand the definition of CDI to determine if they have a covered contractor information system.

DFARS 252.204-7012(a) defines CDI as “controlled technical information” (CTI) or other information described in the CUI registry.

- Based on this, a contractor must understand the definition of CTI to determine if they have any CDI.

DFARS 252.204-7012(a) defines CTI as information that meets the DoD Instruction 5230.24 criteria for distribution statements B through F.

- Based on this, a contractor must understand the criteria from DoD Instruction 5230.24 to determine if they have any CTI.

DoD Instruction 5230.24 section 4.3(a) tells us that CTI is a category of CUI.

- We already know that CUI should be marked, so we could stop here with the conclusion that a contractor that is not receiving marked CUI is not receiving any CTI.

- For a more formal definition, that same section defines CTI as “technical information with military or space application that is subject to controls on access, use, reproduction, modification, performance, display, release, disclosure, or distribution.”

- Section 4.3 and Table 1 provide more information on the different categories of information and the applicable distribution statements.

Putting this all together we can show that, even though a contractor received a contract with a DFARS 252.204-7012 clause:

- A contractor that is not receiving or creating information marked as CUI (either CTI or other categories of CUI) under this contract does not have what DFARS 252.204-7012 considers to be CDI.

- Without CDI, there are no covered contractor information systems.

- Without covered contractor information systems, there is no obligation to implement the NIST SP 800-171 controls for the protection of CUI (under this contract at least).

Framework Misapplication

Clauses that demand the use of frameworks intended to protect CUI are also often inserted into contracts in a misguided attempt to gain security assurances by organizations that do not understand how these compliance frameworks are intended to be used, or organizations that are taking the lazy approach of putting every compliance framework they can think of into every contract instead of taking the time to determine which requirements are applicable to each specific contract.

NIST SP 800-171 seems to be frequently abused in this fashion. Many state, local, and private sector organizations that have no federal contracts seem to think that NIST SP 800-171 is a generic Information Security framework that they can use to ensure their partners have adequate Information Security controls. This is an inappropriate use of NIST SP 800-171 because it was designed specifically for the protection needs of CUI and may be insufficient to protect other information that is more sensitive than CUI or may be an unnecessary burden for information that is not as sensitive as CUI. Furthermore, because NIST SP 800-171 controls specifically refer to the protection of CUI, parts of the framework make no sense when applied in a context where there is no CUI to protect.

To make this as clear as possible:

- CUI protection obligations only flow down in agreements that originated with executive branch agencies of the United States Federal government.

- State governments, local governments, and other private organizations should not have CUI protection clauses in their contracts unless those contracts are part of the supply chain for and involve the handling of CUI on behalf of a United States Federal government executive branch agency.

- CUI can only be created and designated by or under a CUI protection agreement with a United States Federal government executive branch agency.

- State governments, local governments, and other private organizations cannot create or designate CUI unless they are operating under such an agreement and the information meets the definition of CUI from 32 CFR 2002.

- NIST SP 800-171, NIST SP 800-172, and CMMC are all frameworks specifically created for the protection of CUI on non-Federal systems (including contractors) by organizations that have CUI protection agreements with United States Federal government executive branch agencies.

- State governments, local governments, and other private organizations should never require a contractor to use these frameworks in any context other than the protection of CUI on non-Federal systems under an agreement with a United States Federal government executive branch agency and these frameworks are meaningless outside of this context as their controls explicitly refer to the protection of CUI.

- NIST SP 800-53 and FedRAMP are frameworks specifically for the protection of United States Federal government information (which may include CUI) in systems operated by or on behalf of United States Federal government executive branch agencies.

- State governments, local governments, and other private organizations should never require a contractor to use these frameworks in any context other than systems operated by or on behalf of United States Federal government executive branch agencies and are meaningless outside of this context as their controls explicitly refer to processes that are exclusive to the United States Federal Government.

Contractors should push back on organizations that are sending out contracts with “fake” NIST SP 800-171, NIST SP 800-172, NIST SP 800-53, CMMC, and FedRAMP clauses. See my previous post on compliance framework misapplication for more information on the phenomenon of inappropriate contract clauses and what organizations can do about it.

Cloud Service Applicability

The applicability of the CUI program to cloud providers is a special case because of how the government treats cloud providers. We must divide cloud services into two types: those directly contracted by agencies and those used by contractors with a CUI protection agreement.

Government Cloud Service Contracts

The government considers cloud services used by agencies to be “IT services or systems operated on behalf of the government”. The concept that a cloud service is an entire system operated by a contractor on behalf of the government is an important distinction when compared to traditional contractors that use systems that the contractor owns or controls (potentially including third-party cloud services) to handle information on behalf of the government.

Contractors that are providing cloud services to agencies should be aware of their status as a cloud service provider as agencies would need the cloud offering to have a FedRAMP Authorization (similar to but different from the CUI protection agreement necessary before an agency sends CUI to a contractor).

Organizations that would like to provide services to the government but are unsure whether they are considered a cloud service provider should review the definition of a cloud service in NIST SP 800-145 to make a determination.

Contractors that happen to use third-party cloud services to handle CUI are not themselves subject to the FedRAMP Authorization requirement. If a contractor is using the cloud service as they would use their own systems, then they are simply a contractor using a cloud system, not a contractor operating a system on behalf of the government. Guidance for contractors that use cloud services to handle CUI is in the next subsection.

Cloud services used by the government, including cloud services that handle CUI, are subject to NIST SP 800-53 security controls applicable to government systems rather than the NIST SP 800-171 controls used for non-Federal systems that handle CUI. FedRAMP allows cloud service providers to be assessed against applicable NIST SP 800-53 controls in order to gain the Authorization required to process government information. FedRAMP Authorization is separate from the contractor-focused portion of the CUI program described in this post and a FedRAMP Authorization at the moderate baseline is usually sufficient for a cloud service to handle CUI for the government.

Cloud service providers planning to work with a federal agency should keep their eyes open for my future post on FedRAMP to understand the process of gaining an Authorization.

Contractors Using Cloud Services

Contractors with CUI protection agreements are responsible for safeguarding CUI anywhere it is handled, including cloud services used by the contractor to handle CUI. To put it another way, handling CUI on a third-party system is not a loophole that eliminates the contractor’s CUI protection obligations. Contractors will need to ensure their use of cloud services to handle CUI meets all of the applicable controls in NIST SP 800-171 and/or any other obligations imposed by the CUI agreement.

Contractors will find that many cloud services are not capable of implementing the controls required to safeguard CUI. For example, Microsoft has a blog post that indicates their commercial cloud offerings are not suitable for the protection of CUI. Performing due diligence prior to using a cloud service to handle CUI is essential to make sure the provider supports the necessary controls and does not impede compliance. Contractors that are new to the CUI program may need to change their business processes and/or systems so that they can use compliant cloud service providers or on-premises systems to handle CUI when this is not possible using current non-compliant cloud service providers.

Some cloud services are specifically marketed for government clients and contractors, e.g., AWS GovCloud and Microsoft Government Community Cloud (GCC). Cloud services authorized at the FedRAMP Moderate or higher baseline are also usually acceptable for handling CUI because NIST SP 800-171 is based on the same NIST SP 800-53 Moderate baseline as the FedRAMP Moderate baseline (refer to the specific agreement for details). Government-focused marketing and FedRAMP authorization are both good indicators that the cloud service will be able to support the necessary CUI protection controls, but do not automatically make the service and contractor compliant with NIST SP 800-171 or other agreement requirements. Typically, the contractor will need to configure their cloud instance in specific ways and implement process controls around the cloud service to achieve compliance. Cloud service providers may be able to provide guidance to help contractors understand and implement their responsibilities as they relate to the cloud offering.

Defining compliance responsibilities is a key step when any third-party, including a cloud service provider, is involved in a compliance program. Contractors should document which controls are the responsibility of the service provider, which controls are the responsibility of the contractor itself, and which controls are a shared responsibility between the contractor and service provider. For all controls, but especially shared controls, contractors should also document how each party implements its responsibilities. Some controls may not be applicable to either party and a justification should also be documented. The division of responsibilities are usually documented in the contractor’s System Security Plan (SSP) as required by NIST SP 800-171.

As a simple (and incomplete) example of how responsibilities can be assigned, consider a contractor using an IaaS cloud-based virtual server that will be used to process and transmit but not store CUI:

- The cloud service provider will be responsible for physical security controls (NIST SP 800-171r2 3.10) because the contractor has no physical control over the datacenter where the cloud infrastructure is hosted.

- The contractor will be responsible for access controls (NIST SP 800-171r2 3.1) because the cloud service provider has no knowledge of which of the contractor’s personnel should have access to the server and what access privileges those personnel should have to on the server.

- Both the cloud service provider and the contractor will have shared responsibility for Incident Response controls (NIST SP 800-171r2 3.6) because the CUI could be affected by incidents occurring at the cloud service provider, e.g., a physical breach of the datacenter where the server resides, or with logical access to the server that is outside the cloud service provider’s control, e.g., an authorized user at the contractor leaks their password during a phishing attack.

- Neither party would be responsible for media protection (NIST SP 800-171r2 3.8) because the server is not storing CUI and therefore there is no media containing CUI that needs protection.

The end goal for the contractor is to ensure that the CUI is protected according to the agreement regardless of wherever it is handled, including cloud services.

Defining CUI

Now that we know who CUI protection obligations apply to, the official definition of CUI from 32 CFR 2002.4(h) is our key to understanding what is and is not CUI.

We can break this definition down into parts based on the three sentences within the definition:

- What is CUI

- What is not CUI

- How to protect CUI

The following subsections cover each of these parts/sentences of the CUI definition.

What is CUI

Breaking down the first sentence of the CUI definition:

Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) is information the Government creates or possesses, or that an entity creates or possesses for or on behalf of the Government…

This gives us a clear starting point: Information can only be CUI from a contractor’s perspective if the contractor receives the information from the government or creates the information for the government (including via other contractors in the supply chain).

Any CUI a contractor receives from the government should be obvious because the government has strict and detailed marking requirements for CUI. Information created for the government that qualifies as CUI is more nuanced and will be addressed in detail later in this post.

To understand what information can be designated as CUI (by the government or a contractor) we must review the next part of the sentence:

…that a law, regulation, or Government-wide policy requires or permits an agency to handle using safeguarding or dissemination controls.

This part of the definition sets some parameters on what must and cannot be designated CUI. Specifically, there must be some type of safeguarding or dissemination controls from outside the CUI program that apply to the government’s own handling of the information for it to be designated CUI.

A safeguarding control would describe the security techniques an agency must use to protect a particular category of information while a dissemination control would limit with whom and under what circumstances the agency can share that information.

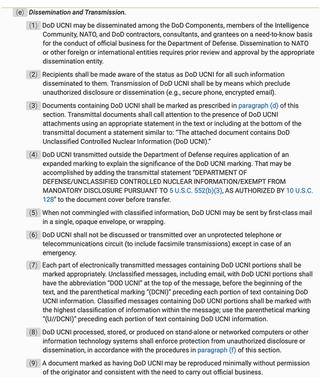

An example of safeguarding and dissemination controls can be found in 32 CFR 223, which addresses DoD Unclassified Controlled Nuclear Information (UNCI): 32 CFR 223.6(e) describes the applicable dissemination controls and 32 CFR 223.6(f) describes specific safeguarding requirements.

An important distinction is that these controls must apply to the government itself to support a CUI designation. Laws and regulations that directly require private organizations to safeguard or control dissemination of information do not automatically create CUI or impart any CUI protection obligations on the private organization (including contractors).

There may be some overlap between the CUI program and the laws and regulations that apply to private organizations. This occurs when there is law or regulation that requires private organizations to protect a certain type of information and another law, regulation, or government-wide policy requires the government to protect that same information. More on that topic later in this post in the section on Regulatory Overlap.

What is not CUI

Continuing with a breakdown of the second sentence of the CUI definition:

However, CUI does not include classified information (see paragraph (e) of this section)…

This is very straightforward: Classified information cannot be CUI. The classification program is completely separate from the CUI program and classified information must be handled in accordance with 32 CFR Part 2001 rather than 32 CFR Part 2002. However, some documents may contain a mix of CUI and classified information. Mixed CUI and classified information markings are covered later in this post.

The remainder of this sentence is of great importance to contractors:

…or information a non-executive branch entity possesses and maintains in its own systems that did not come from, or was not created or possessed by or for, an executive branch agency or an entity acting for an agency.

Defining a few terms from this statement:

- A “non-executive branch entity” as defined in 32 CFR 2002.4(gg)is any organization that is not part of the executive branch of the United States Government, i.e., you work for a non-executive branch entity unless your ultimate boss is the President of the United States of America (POTUS).

- An “executive branch agency” includes anyone whose ultimate boss is the POTUS, even if they work for a department, bureau, office, or some other part of the government that does not have “agency” in its name (This does not include the legislative or judicial branches of the government).

- An “entity acting for an agency” is essentially a non-executive branch entity that holds an agreement with an executive branch agency, e.g., a government prime contractor that has a CUI protection agreement with an agency or any other subcontractors in the supply chain with appropriate CUI agreements in place.

This part of the definition is explicitly restating from another perspective what we already learned by reading the first sentence of the definition: any information that a non-executive branch entity (e.g., a contractor) has in its own systems is not CUI unless it meets at least one of these criteria:

- It came to the contractor from an agency or entity that has a CUI agreement with an agency.

- It was created by the contractor for an agency or entity that has a CUI agreement with an agency.

- It is possessed by the contractor for an agency or entity that has a CUI agreement with an agency.

How to protect CUI

Concluding with a breakdown of the third sentence of the CUI definition:

Law, regulation, or Government-wide policy may require or permit safeguarding or dissemination controls in three ways:

This tells us that not all CUI is created equal. The various legacy safeguarding and dissemination controls that the CUI program absorbed contain different levels of detail. To deal with this, the CUI definition creates two different types of CUI and a hybrid between those two types.

The first type is CUI Basic, for use when the laws, regulations, or government-wide policies state that information must be protected but provide no specific details:

Requiring or permitting agencies to control or protect the information but providing no specific controls, which makes the information CUI Basic;

The second type is CUI Specified, used when the laws, regulations, or government-wide policies contain extensive detailed control information:

…requiring or permitting agencies to control or protect the information and providing specific controls for doing so, which makes the information CUI Specified;

And the third hybrid type is also CUI Specified, used when the laws, regulations, or government-wide policies contain some detailed control information but not a complete set, in which case CUI basic controls are used for the remaining undefined controls:

…or requiring or permitting agencies to control the information and specifying only some of those controls, which makes the information CUI Specified, but with CUI Basic controls where the authority does not specify.

How these types of CUI affect contractors is described in 32 CFR 2002.14(h)(2), which addresses the protection of CUI. According to this regulation, agencies must require contractors to use NIST SP 800-171 to protect CUI Basic on “non-Federal” (e.g., contractor) systems. Federal agencies may deviate from the NIST SP 800-171 requirement for contractors in only two circumstances:

- The information is CUI Specified, in which case the safeguarding and/or dissemination controls specified in the applicable laws, regulations, and government-wide policies must be used instead.

- There is an agreement with the contractor to protect the CUI Basic at a level higher than the moderate confidentiality baseline.

“Moderate confidentiality baseline” is a reference back to NIST SP 800-53, the set of security controls that federal agencies are required to use to protect their own systems under FISMA. NIST SP 800-53 contains three (3) security baselines: low, moderate, and high. FIPS 199 is the standard that government agencies use to determine which of these baselines is appropriate for a particular category of information and FIPS 200 establishes the minimum security requirements for information at each baseline. NIST SP 800-171 was based on the NIST SP 800-53 moderate baseline as moderate confidentiality was deemed appropriate for CUI Basic safeguarding.

Creating CUI

As mentioned above, contractors operating under an agreement with a government agency can create CUI. However, this does not mean that all information created for the government is automatically CUI, or that the information is CUI from the perspective of the contractor even if it is CUI from the perspective of the government.

The NARA CUI FAQ states that industry (i.e. contractors) are only required to mark CUI when instructed to do so in a contract or supporting document. There must also be a lawful reason for the information to be marked as CUI, which brings us back to the part of the CUI definition that states a law, regulation, or government-wide policy that applies to the information is required for the information to be designated CUI. This means that a contractor usually does not need to designate, mark, or protect the information they create as CUI unless they have been specifically instructed to do so as part of their contract and its supporting documents.

Descriptions of the contractor created information that must be marked as CUI may come in a few different forms. Documents that are used to describe contractor information that must be classified are also being used to describe information that must be designated CUI, e.g., Security Classification Guides or the DoD DD Form 254 Contract Security Classification Specification.

In some cases, instructions to mark contractor-created information as CUI may be missing or unclear. This may be because:

- The CUI clause may be in place because the government will only be sending CUI to the contractor and does not consider any information created by the contractor to be CUI (at least from the perspective of the contractor).

- The agency is required to add a CUI clause to contracts even if no CUI will be handled under the contract, e.g., the DFARS 204.7503 (b) instruction to insert the CMMC contract clause into solicitations and contracts for all commercial products and services except for off-the-shelf items with no mention of whether or not CUI will be handled.

- Government contracting personnel are only human and make mistakes. They may have unnecessarily included a CUI clause in a contract or may have forgotten to include a schedule of CUI that will be created under the contract.

There are a few methods to determine if the information a contractor is creating under a contract is likely to be CUI, each covered in a subsection below:

- Making assumptions.

- Asking for clarification.

- Researching the applicable laws, regulations, and government-wide policies (source material).

Contractors may also decide they want to voluntarily designate and mark their own information as CUI before sending it to the government to force protection of their own sensitive information, which is covered in this section as well.

Making Assumptions

Perhaps the most common scenario where a contractor may create CUI is when they are re-using, restating, or paraphrasing existing CUI or other sensitive information that has since been merged into the CUI program. In these cases, it can be assumed that the product of such efforts is also CUI and should be designated, marked, and protected as such.

Asking for Clarification

There are agency resources that can help when it is not clear whether newly created information will be considered CUI. The best place to start is the Contracting Officer (CO) for the Government Contracting Activity (GCA). The CO should be able to assist with an understanding of the CUI that will be created.

Generally, the contractor will be reaching out to the Dissemination Authority (the agency that is potentially distributing CUI) rather than the Designation Authority (the agency that designated the information as CUI) when the same agency is not performing both of these roles.

Unfortunately, this avenue may not be available to subcontractors far down the supply chain as the GCA and CO do not necessarily know the details of subcontracts. In theory, prime contractors should be responsible for working with the GCA to answer any CUI questions, but many subcontractors have reported difficulty getting other contractors in the supply chain to cooperate.

Reviewing Source Material

As stated in the definition of CUI, information can only be designated CUI if there is a law, regulation, or government-wide policy that requires the government itself to protect the information. Contractors with no other viable options can check to see if there are any laws, regulations, or government-wide policies that apply to the information in question and determine whether the information in question is likely to be CUI based on the results. Accurately making this determination will likely require the participation of legal counsel.

Keep in mind, this process for identifying potential CUI should be a last resort: all CUI received from the government should be clearly marked and contract documents should clearly indicate which information created by the contractor must be designated as CUI. Contractors should try to get questions answered by agencies and prime contractors before using this technique to identify potential CUI.

The NARA CUI Registry is the primary source for making this determination. Contractors can use the Category Description contained in the registry to determine which CUI categories are most likely to apply to the information in question. The entry for each category contains a Safeguarding and/or Dissemination Authority section with links to the laws, regulations, and government-wide policies that apply to information in that category and, therefore, require the information to be designated as CUI. Reviewing these source documents can help determine if a piece of information belongs in a specific CUI category based on whether and how the listed laws, regulations, and/or government-wide policies apply to the information.

Consider the following scenario:

- An architect-engineering firm is designing a new building for the federal government and has a contract with the General Services Administration (GSA) (an agency) that includes a CUI clause.

- The firm is concerned that their building drawings may be considered CUI but has been unable to get a clear answer.

- Upon reviewing the CUI category descriptions in the NARA CUI Registry, the firm determines that the category, CUI//PHYS may be applicable to their drawings because it relates to the protection of federal buildings, grounds, or property.

- The Safeguarding and/or Dissemination Authority table links to a GSA order, GSA PBS P 3490.3.

- The firm finds section 4(c) of the GSA order, as shown in the screenshot below, that describes CUI designations for building drawings.

After a first glance at this section, the firm concludes that their information may be considered CUI under the CUI//PHYS category as the document states that the drawings and other related building information for new facilities owned by the government ‘must be designated CUI, as appropriate’. However, there is a grey area because:

- The section uses the qualifier “as appropriate” and refers to another section of the document that contains more information to determine what is an appropriate designation.

- The section concludes with a statement that “not all building information should be designated as CUI”, clearly indicating that there is some leeway here.

Based on these points, the organization could dig deeper into the document to determine what the GSA considers an appropriate designation of CUI.

Before digging deeper into the document though, we should take notice of the part of section 4(c) that tells us the CUI designation occurs “when the information is turned over by the architect-engineering (A-E) personnel to the Government as part of the final approved concept documents.” This seems to indicate that the drawings are not CUI while the firm is drafting them and, therefore, a reasonable person could conclude that the firm does not need to worry about the details of whether a CUI designation is appropriate for their particular drawings (the government will make that determination once the final approved concept documents have been turned over).

This scenario illustrates a very important point about CUI: Just because information is CUI to the government, this does not necessarily mean it is CUI to the contractor. In this case, the contractor is creating a document that will be CUI to the government but not to the contractor because of the way the government-wide policy that applies to this information is worded: the information is only designated CUI after it is turned over to the government, not while it is in possession of the firm.

This is only one simple and narrow example out of many types of information that could be CUI, and the author is basing the analysis above based on a plaintext reading of the linked sources. Each contractor’s agreement, information, context, and applicable source materials are different. Contractors will need to conduct a similar detailed analysis of the text of the laws, regulations, and government-wide policies applicable to their unique situation and are encouraged to get assistance from their legal team to determine whether and how the source materials apply to the information they are handling.

Protecting Contractor Information with CUI Designations

The concept from the previous section, that information may not be CUI for the contractor even if it is considered CUI by the government, is a powerful tool that contractors can wield to protect their own information.

Contractors may find themselves in a position where they must share what they consider sensitive proprietary information with the government and the government may, in turn, need to share that information with other contractors. Contractors that are worried about the spread of their proprietary information can voluntarily mark the information as CUI, thereby forcing the government and other government contractors to safeguard the information and limit its dissemination. This is often useful for contractors that must share trade secrets, designs, software source code, research and development products, etc.

Keep in mind, marking information in this manner before sending it to the government does not create any CUI protection obligations for the contractor itself. This is the contractor’s information to do with as they please, the contractor is just leveraging the CUI program to force the government and other contractors to protect their sensitive information.

In order to protect contractor information with CUI markings, we must go back to the CUI definition that states a law, regulation, or government-wide policy must apply to the information in order to support a CUI designation. Contractors can use the Reviewing Source Material process described in the previous section to identify the supporting laws, regulations, and policies that apply to the information they want to protect and then apply the appropriate CUI category markings to the information before sending it to the government.

A common CUI category used for this purpose is CUI//PROPIN or CUI//SP-PROPIN, which is used to protect “Material and information relating to, or associated with, a company's products, business, or activities, including but not limited to financial information; data or statements; trade secrets; product research and development; existing and future product designs and performance specifications.” There are a wide variety of laws, regulations, and policies that require the government to protect this category of CUI, some of which are CUI Specified, so it is almost certain that a contractor can find something that applies to their information.

Be sure to use the official and appropriate CUI markings when designating CUI. CUI marking guidance is described in further detail below.

CUI Markings

As previously described, CUI received from the government should be clearly marked. Understanding what a legitimate CUI marking looks like will help contractors determine what really is CUI. Understanding CUI markings is also essential for contractors that will create CUI that must be marked correctly.

Official Markings

32 CFR 2002.20 is the definitive source of information on how CUI must be marked but, as with most government regulations, this is a wall of text that can be hard to visualize. The NARA CUI Marking Handbook provides visual examples of how documents, media, and physical spaces that contain CUI must be marked. There is also a DoD CUI Markings document that provides some more useful examples of email and slides markings as well as Designation Indicators.

In general, document markings (including both electronic and printed media) include:

- A standardized coversheet (usually optional).

- A mandatory CUI banner marking on each page of the document (usually in the header and footer) that contains:

- A mandatory Control Marking that states either “CUI” or “CONTROLLED”.

- CUI category or subcategory markings from the CUI Registry (optional for CUI Basic, mandatory for CUI Specified).

- Limited Dissemination Control markings from the CUI Registry if applicable.

- A mandatory Designation Indicator that indicates who designated the information as CUI.

- Portion markings where only certain parts of a document contain CUI.

Documents may also be marked with Decontrolling Indicators. These may include a date or event after which the information is no longer considered CUI regardless of other markings. Agencies and contractors are no longer obligated to protect the information as CUI once the date or event occurs regardless of other CUI markings.

The NARA CUI registry is also the resource for looking up and understanding the CUI category, subcategory, and limited dissemination controls marked on the document.

The NARA CUI registry contains some additional tools, useful for marking CUI including:

- An approved coversheet template, that can be useful when marking CUI.

- A guide to marking emails.

- A guide to marking audio, photography, and video materials.

- Links to purchase approved labels for marking physical media.

As with anything, there are exceptions to CUI markings. 32 CFR 2002.20(a)(8) provides for situations where it is impractical for an agency to individually mark CUI due to the quantity or nature of information. For example, it may be difficult to mark individual data fields that contain CUI within a database. When this occurs, agencies are required to provide some sort of readily apparent alternate marking, e.g., an access agreement or splash screen, that notifies personnel of the CUI status of the data.

Agencies may apply various waivers allowing them to avoid marking CUI but these waivers only apply while the CUI is in possession of that agency. 32 CFR 2002.38(d)(3) states that waivers may not be applied when CUI is disseminated outside their agency (e.g., to a contractor).

Legacy Markings

Contractors should no longer receive information with legacy markings that predate the CUI program. 32 CFR 2002.20(a)(1)(i) requires agencies to discontinue use of legacy markings and 32 CFR 2002.36(a) requires agencies to re-mark any documents that contain information that is now part of the CUI program. 32 CFR 2002.36(b) allows for agencies to receive waivers when re-marking legacy material is deemed excessively burdensome, but this legacy marked material should not make its way out to contractors because 32 CFR 2002.38(b)(1) states that the waiver only applies while the CUI remains under agency control.

Organizations may also deal with legacy markings such as For Official Use Only (FOUO) or Sensitive but Unclassified (SBU) as a result of agreements that predate the CUI program. It is important to remember that CUI and its predecessor requirements are imposed on contractors via agreements with government agencies. The existence of the CUI program does not automatically change a contractor’s pre-existing agreements and obligations regarding information it received under those older agreements. 32 CFR 2002.16(a)(5)(iv) instructs agencies to modify information sharing agreements that pre-date the CUI program when feasible. Contractors must continue to handle legacy marked information received under prior agreements in accordance with the agreements under which the information was received until the contractor receives an updated agreement.

Unmarked, Unnecessarily Marked, or Incorrectly Marked CUI

Contractors may receive information that:

- They suspect is CUI even though it does not bear CUI markings.

- Bears CUI markings even though they suspect it is not CUI.

- Bears CUI markings that do not align with the CUI category of the information.

The Reviewing Source Material process described earlier in this post can help a contractor confirm or refute their suspicions related to whether information is CUI and whether it is appropriately marked.

Contractors should reach out to the agency that disseminated the information if suspicions about inappropriately marked CUI are confirmed. Each agency should have a process for handling these reports in accordance with 32 CFR 2002.50(c). This includes acknowledging receipt of the report and providing contact details and a timeline for resolution. The information should be protected as if it is CUI until the issue is resolved.

Unsolicited CUI

Some contractors have reported receiving RFPs or other documents that appear to be CUI prior to having a CUI protection agreement in place. Contractors have also reported receiving CUI via methods other than the channels they have set up to handle CUI.

There are plausible explanations for this, e.g., if a contractor voluntarily marked their own sensitive information as CUI before providing it to the government there is nothing preventing that contractor from sharing that same information with other organizations, it is their information after all. It is sloppy and confusing practice to privately share a CUI marked version of information when CUI protection obligations don’t apply though.

Otherwise, contractors should not receive CUI directly or indirectly from the government without a protection agreement in place. Keep in mind, each contract is usually a separate self-contained agreement so even a contractor that has a past or current contract that includes a CUI protection clause should not be receiving CUI unrelated to that contract unless there is some sort of blanket CUI protection agreement in place.

Many contractors have set up specific channels for receiving CUI, e.g., a file sharing portal, and have prohibited the use of other channels for CUI transmission, e.g., email. This is often done to minimize compliance scope and/or to avoid handling CUI on systems that cannot be made compliant. Contractors should include contract clauses requiring other organizations to exclusively use their authorized CUI channels and make these expectations clear when establishing points of contact. If an agency sends CUI via an unauthorized channel that does not have CUI safeguards in place they may be violating the 32 CFR 2002.16(c)(1) requirement to disseminate CUI a method that meets the safeguarding requirements.

When a contractor receives unwanted CUI or receives CUI via an unauthorized method, the contractor should immediately and securely delete the CUI and then notify the sender of the error. Contractors may also consider activating their Incident Response plan. 32 CFR 2002.16(a)(6)(iii) states that CUI agreements with contractors must require reporting of non-compliance with handling requirements to the disseminating agency.

As with most things in the CUI program, the non-compliance reporting details will be specific to each agreement. As an example, the General Services Administration (GSA) CUI Program Guide states that contractors are responsible for reporting incidents to a specific email address and contains a list of reportable CUI incidents that potentially includes the scenarios described above. Meanwhile, the DoD’s DFARS 252.204-7012 CUI protection clause requires reporting incidents to the DoD within 72 hours via a specific website.

Regulatory Overlap

There are many scenarios where information may fall within the CUI program and may also be covered by other laws or regulations outside the CUI program. Contractors need to understand the context in which they handle information to determine whether the CUI program or other laws and regulations apply (or both). The concept that information may be CUI to the government but not to a contractor is important to remember when making this determination.

Consider the following scenario to illustrate the concept of mixed laws, regulations, and CUI:

- A doctor creates a patient record, not specifically for the government.

- The doctor sends the patient record to an agency for some lawful purpose, e.g., an infectious disease control report.

- The agency sends the patient record to a contractor for some lawful purpose, e.g., statistical analysis of infectious disease outbreaks.

In the scenario above:

- From the perspective of the doctor:

- The doctor is a Covered Entity under HIPAA (which has nothing to do with CUI) as defined in 45 CFR 160.103

- The patient record meets the HIPAA definition of PHI from 45 CFR 160.103

- The doctor protects the patient record in accordance with the HIPAA Security and Privacy rules applicable to Covered Entities handling PHI as described in 45 CFR Part 164.

- From the perspective of the agency:

- The patient record is health information as defined in 42 USC 1320d(4).

- There are a variety of laws, regulations, and government-wide policies that apply to the patient record as shown in the CUI registry entry for Health Information.

- The agency designates the patient record as CUI (likely CUI//HLTH depending on the nature of the patient record and its contents) and handles it using the controls from the NIST SP 800-53 Moderate Security baseline.

- The agency must have a CUI protection agreement in place with any contractors prior to sending the patient record because they would be sending CUI to a non-executive branch agency.

- From the perspective of the contractor:

- The contractor signs a contract with the agency that contains a CUI protection agreement.

- The contractor receives the patient record marked as CUI from the agency.

- The patient record is CUI while in the contractor’s possession because it is marked as CUI and is handled on behalf of an agency under a CUI agreement.

- The contractor protects the patient record using the NIST SP 800-171 controls in accordance with the CUI agreement.

- The contractor must pass on the CUI protection obligations in contracts with any parties they share the patient record with, e.g., cloud service providers they use to perform statistical analysis.

Note that:

- The fact that the agency designated the patient record as CUI does not impart a CUI protection obligation on the doctor because the doctor does not have an agreement with the government to protect CUI, did not create the patient record for the government, and does not possess the record on behalf of the government. The doctor uses the HIPAA Security and Privacy rules that are directly applicable to Covered Entities handling PHI to protect the patient record rather than the NIST SP 800-171 controls for CUI on non-Federal information systems.

- Conversely, the contractor implements the NIST SP 800-171 controls rather than the HIPAA Security and Privacy rules because the contractor does not meet the legal definition of a Covered Entity that would result in HIPAA compliance obligations.

- The contractor uses NIST SP 800-171 to protect the CUI while the government uses the NIST SP 800-53 Moderate Security baseline because NIST SP 800-171 is for non-Federal systems while NIST SP 800-53 is for Federal systems.

Each of these organizations is protecting the same information in a different way because of their specific relationship with the information and the applicable laws, regulations, and policies.

What About FCI?

Federal Contract Information (FCI) and the FCI program for contractors is similar to the CUI program, which leads to some confusion. FCI is a broader category than CUI with much less stringent controls. CUI can be thought of as a type of FCI, i.e., all CUI is FCI but not all FCI is CUI.

Much like the CUI program, FCI safeguarding requirements are imposed by contract clauses. In this case, FAR 4.1903 instructs contracting personnel to insert the clause at FAR 52.204-21 into contracts when the contractor may have FCI residing in or transiting through its information systems. These contract clauses impart compliance obligations on contractors.

The FAR 52.204-21 clause contains a set of 15 basic safeguards for FCI. These 15 safeguards are also part of the NIST SP 800-171 controls for CUI, which makes sense because all CUI is also FCI and should be safeguarded using the FAR 52.204-21 basic safeguards plus additional CUI safeguards. It’s worth noting that FAR 52.204-21 explicitly states that compliance with this clause for FCI does not relieve contractors of their other agreed obligations to protect CUI.

The formal definition of FCI is as follows:

…information, not intended for public release, that is provided by or generated for the Government under a contract to develop or deliver a product or service to the Government, but not including information provided by the Government to the public (such as on public websites) or simple transactional information, such as necessary to process payments.

We find similarities once again: Information cannot be FCI unless it is provided by or generated for the government under a contract.

The key part of the FCI definition is that it must be information that is not intended for public release. Any information that came from a public source or that the government releases to the public cannot be FCI.

Because the definition of FCI is so broad and the safeguards are so basic, TrustedSec recommends contractors treat all information that is not publicly available as FCI and apply the 15 basic safeguards from FAR 52.204-21 across all of their systems that handle or create information for an agency.

Implementing a CUI Program

Contractors that are looking to become involved in government contracts that may require handling CUI should begin their CUI Program by thinking about:

- What agencies are likely to be sending them CUI so they can review the specific CUI contract clauses used by that agency.

- The types of CUI they may be likely to receive or create so they can determine whether the basic NIST SP 800-171 controls are sufficient or what specific controls for that CUI are required.

- How they can adjust their business processes to minimize the impact of CUI program compliance on their operations, i.e., limit the people, locations, and systems that handle CUI to the smallest number possible.

- Building an environment that aligns with NIST SP 800-171 or other specified controls so they are ready to handle CUI when a contract arrives.

Developing a CUI program always begins by documenting a System Security Plan (SSP) that includes the details of the in scope system and all applicable security controls. This requires knowledge of how the data will flow through business process, systems, and networks. This is a followed by documenting a Plan of Action and Milestones (POA&M) describing how and when compliance gaps will be addressed. Once the applicable controls have been implemented, the organization will be ready to be awarded contracts that required handling of CUI.

TrustedSec has experience helping organizations prepare for Federal contracts that include FCI and CUI, as well as working directly with Federal organizations to meet their FISMA and NIST SP 800-53 obligations. Please reach out if you still have questions to see how we can help.